Blog Archives

Consano Pelvic Health Centre is sponsoring ABREAST Conference 2023!

Consano is proud to be sponsoring the ABREAST conference in November 2023 presenting the latest research and science in breastfeeding and lactation.

Over many years our practitioners at Consano have sought to learn and uphold the best evidence-based practice, supporting mums to breastfeed. We are grateful to live in Perth, where we have a world-leading human lactation research team to guide us. Join members of the team and other professionals on Friday 10th November to explore the latest research and science relating to lactation. Follow this link for more information and to register: The Australian Breastfeeding + Lactation Research and Science Translation Conference 2023 (hopin.com)

ABREAST Conference 2023

Friday 10th November

9:00AM – 5:00PM GMT+8

AUSTRALIAN BREASTFEEDING + LACTATION RESEARCH AND SCIENCE TRANSLATION Conference!

Australia has an exceptional reputation for world class human lactation research, spanning from breastfeeding experiences to milk composition and production, through to how milk impacts our babies.

We are excited to showcase this cutting-edge Australian research alongside outstanding international and national speakers.

Together we aim bring diversity, passion and innovation to lactation research that makes positive impacts on mothers, babies, and communities worldwide.

The symposium is OPEN TO ALL, from researchers to clinicians to the community. Registrations are available to attend in person at The University Club of Western Australia, or join us live virtually.

All registrations will have access to the recording of the full days presentations.

We look forward to rich interactions and hope you can join us in 2023!

Common (medical) testing of the bowel -what the tests involve and why they are done

How are the results presented?

Vaginismus leaves many women in pain and avoiding sex, but it can be treated

Recently our practice principal and clinic director, Alison Wroth, was interviewed by ABC news journalist Grace Burmas. Well done, Grace, for shining a light on a sensitive and distressing issue that is common to many women’s experience.

ABC article –

Navigating pain for women can be a twisted maze of questions, referrals and specialists, but amid the ever-growing list of diagnoses lies a silent condition that is experienced by many.

It’s called vaginismus.

Six months ago, Sophie*, 22, started to endure painful sex with her long-term partner.

“It’s just like a heavy pressure,” she said.

“I thought it was because I left it too long, like a month between intercourse, but then that shouldn’t really change anything.

“I was looking for answers with the gynaecologist being like ‘it must be PCOS’ (polycystic ovarian syndrome), but PCOS doesn’t actually cause pain.

” I think I was just looking for a reason because I didn’t want it to be vaginismus.”

What is vaginismus?

Vaginismus is when vaginal muscles involuntarily contract in anticipation of penetration.

It causes immense pain or discomfort during intercourse, physical examinations or inserting a tampon and is psychologically triggered.

Those triggers vary greatly, from a general fear of penetration, to medical conditions like endometriosis, to a past trauma such as sexual assault or a distressing childbirth.

Equal to the physical pain can be the emotional toll it takes on women, the isolation they feel and the pressure it places on their relationships.

“The anxiety that came with it, because one time would be painful and then if you’d leave it for too long, it would just build up in my head more than anything,” Sophie said.

A cycle of pain

She thinks of vaginismus as a cycle, where one painful experience builds fear for the next time, which feeds the muscle tension and leads to more pain.

“My boyfriend doesn’t feel like I want to be intimate with him, which I do, and then I had to explain to him I get anxious because of the pain, not because of the situation,” she said.

“Him trying to comfort me, but not knowing the language to use, kind of makes me feel worse.

“It’s so tiring having the conversation, it’s exhausting.”

The prevalence of the condition is blurry but health professionals, like sexologist Melissa Hadley Barrett, believe the numbers are much higher because of under-reporting.

“In a clinic like mine it’s between five and 17 per cent … but in the general population, they say between one and six per cent,” she said.

“It’s just not something people talk about, so people don’t know that it even exists until they come across it.”

Ms Hadley Barrett helps women and their partners work through the condition, which she said takes time but is achievable with a comprehensive approach and open communication.

“The partner often blames themselves and I think it’s about getting them to understand that it’s nothing they’ve done, it’s just the person has anxiety around having pain in general,” she said.

“You’re not going to touch a hot oven if it burns you.”

Ms Hadley Barrett said a lot of women try to work around the symptoms of vaginismus instead of seeking professional help.

Like many women’s health issues, knowing where to go can be overwhelming — and there’s often a cloud of shame surrounding sexual complications.

Finding the trigger

Pelvic floor physiotherapist Alison Wroth said along with a psychological approach, health professionals can work to retrain and relax the pelvic floor muscles.

“It’s thought that the pelvic floor muscles have a protective response … it makes sense to think if a woman is feeling unsafe, that these muscles would tense,” she said.

Ms Wroth helps her clients understand what the initial trigger may be and how to address that fear emotionally and then physically.

“I think it’s really confronting to go and see someone about this part of the body,” she said.

“Sometimes even in taking a really thorough history, we don’t really get to what the initial onset was, but we can still work with the body and how it’s responding now.”

Seeking help can be hard

Sophie is yet to seek professional help, because of the barriers a lot of women face when dealing with pain and complex health complications.

“It always puts me off because of the amount of money it costs and it’s intimidating, I don’t know I’ll just cry, but I think it’s worth it,” she said.

“It’s been months of trying to fix it myself, which is not happening.

“As much as I think that I’m in control of it, the brain is just a lot more powerful.”

However difficult treating vaginismus may seem, there is hope in overcoming the condition, Ms Wroth said.

“I’m constantly amazed at humans and the complexity of systems that are all working together just to keep us functioning in the body, and how quickly they can change if that person is ready, with the right practitioners to help them,” she said.

ABC News: Women speak out about birth trauma and poor pelvic health care in public system

Yet hundreds of thousands of Australian women come away from childbirth with damage to their pelvic floor — the group of muscles that hold up organs and control the bladder and bowel.

Currently there is no clear national data on how many women experience these symptoms, but fresh research offers rare insight into the possible scale of the problem.

A two-year study that asked 2,800 women on the Gold Coast about their symptoms following childbirth is about to be published — and the results are alarming.

It found that three months after giving birth:

- one in three women struggle to control their bladder

- one in 10 suffer faecal incontinence and

- one in two experience pain with sex

Valerie Slavin, a midwifery researcher at Griffith University who led the project, says pelvic injury isn’t being addressed because the health system doesn’t ask women about their symptoms.

“It’s just a really neglected area,” she says.

And she says until we start systematically collecting national data about the problem, women will continue to suffer.

‘No-one mentioned prolapse’

The first time Samantha Coughlan became aware of prolapse was when she did an internet search about what she was feeling.

She was out walking with her husband a few weeks after the birth of her first child when she says she felt like her insides were falling out.

Previous studies have estimated half of all women who have given birth experience some degree of prolapse — a condition in which one or more of the pelvic organs drop into the vagina — but there is no clear national data.

“No-one mentioned prolapse. I’d never heard the word,” she says.

That’s despite her daughter being delivered using forceps to pull her through the birth canal, which led to a severe vaginal tear. Both are linked with a higher risk of pelvic floor dysfunction.

The Melbourne mum had given birth in a public hospital, where she was told if she had any problems she could go on a waitlist to see a physiotherapist.

Unwilling to wait, she found a private women’s pelvic physio.

Four years later, Samantha still struggles with activities that strain her pelvic floor, including lifting her kids.

“I want to be that fun mum who jumps on the trampoline … and goes down the slide, but I can’t physically do it,” she says.

The former schoolteacher also experiences urinary incontinence when she coughs or laughs.

“That’s actually stopped me going to work.

“It’s not worth the embarrassment.”

Samantha Coughlan still struggles with activities that strain her pelvic floor, including lifting her kids. ()

Women’s health physiotherapist Lyz Evans runs a clinic in Sydney and says physical birth injuries can be catastrophic.

Women might avoid exercise, leaving the house because they’re not sure where the next bathroom is and intimacy with their partner, she says.

“On a daily basis, I’m sitting … with women in tears. And the impact of that emotion isn’t just to that woman. It affects her partner. It affects her children,” she says.

A ‘hidden epidemic’

The ABC has heard from nearly 4,000 women as part of the Birth Project.

Hundreds of women described devastating pelvic injuries and expressed dismay with the standard of care in the public system.

Many said they resorted to spending thousands of dollars seeing specialist physios in the private sector.

Access to publicly available pelvic physiotherapists across Australia varies from state to state and between urban, rural and remote areas.

Ms Evans believes the rate of pelvic floor trauma is higher than acknowledged and can be dramatically reduced if women were given access to pelvic floor physio before and after giving birth.

“It is a true hidden epidemic in our society that needs to be addressed.”

Physios can help prevent birth trauma by working with women during pregnancy to assess their risk of pelvic injury and help prepare their pelvic floors for labour.

They also help women recover from birth using pelvic floor muscle training and guidance on how to safely return to activities such as exercise.

The Australian Physiotherapy Association (APA) is calling on the federal government to provide all women with five Medicare-funded sessions with a pelvic physiotherapist during their child-bearing year.

Catherine Willis, chair of the APA’s advisory council, says this will help women prevent and recover from birth trauma.

“The cost of five physiotherapy appointments for women birthing in Australia has a much better economic value than the future interventions that they might need, including surgery, and also the inability to return to work due to their pelvic floor symptoms.”

Ms Willis says she’s seen women in their 60s and 70s who have endured pelvic floor problems since the first time they gave birth.

“That’s really sad to think that possibly for 30 or 40 years they’ve been putting up with these symptoms.”

‘Holding women back’

Emma Elder’s second pregnancy put twice as much strain on her body, but sessions with a physio made it a much better experience than her first.

After delivering twins it took her only a few months to return to running and jumping.

Following her first pregnancy, it took two years.

“I found [pelvic physio] extremely beneficial, not just for my recovery, but also for the preparation for birth,” she says.

Several months after giving birth to her first baby, which caused a severe vaginal tear, she was dismayed she couldn’t skip, jump or lift weights at the gym without wetting herself.

“I had to make sure that I was always carrying a spare change of clothes,” she says.

Unwilling to accept a weak pelvic floor as an inevitable and irreversible consequence of childbirth, she spent thousands of dollars on private physios and now wants that available to more women.

“I think this issue really holds women back,” says Emma.

‘What we don’t measure, we can’t improve’

Dr Slavin says one of the reasons women aren’t getting access to better pelvic care is that the scale of the problem is not known.

Australia has a clinical care standard for the 3 per cent of women who deliver vaginally and experience a tear that extends into the muscle of the anus.

Many more women than that experience life-altering pelvic injuries, but there is currently no way to evaluate how many women are affected and no national standard for the care they should receive.

Dr Slavin wants to see the public health system routinely collect data from women about their experience of pelvic floor disorders, as well as the model of care and procedures used during their delivery.

She believes that will drive improvement in maternity care.

“What we don’t measure, we can’t improve on,” says Dr Slavin.

Assistant Minister for Health Ged Kearney says she would be interested in discussing better data collection with her state counterparts.

“Collecting data is an incredibly important part of improving our health system,” she says.

Ms Kearney says many women have told her they don’t feel their experience has been heard and want birth trauma to be taken seriously.

Both Samantha Coughlan and Emma Elder think the first step towards this is rejecting the stigma of talking about pelvic disorders.

“I would love other women to know that there’s nothing to be ashamed of,” Samantha says.

“We need to talk about it so we can make things change.”

Understanding Your Core – Article for Ostomates Magazine 2022

Did you know your abdomen has four layers of abdominal muscle? And that the surface layer, or “six-pack” muscle, runs perpendicular to the deepest layer? I find this fascinating, that a muscle in the same group, and sharing the same location, can run in a completely different direction. This is, of course, because they have different functions. The four layers of abdominal muscle form part of our wondrous myofascial system. Our abdominal muscles synchronise with our diaphragm (breathing) muscle and pelvic floor muscles to form an internal system of support that is often referred to as our “core”. Our core serves an important purpose in maintaining and distributing pressure as we go about everyday life. We rely on this system of connective tissue to move, stand, sit upright, sleep and even breathe. In fact, this interconnecting network of tissues is the reason that when we stand up, our internal organs don’t just drop into the base of our pelvis.

Our internal organs, including the bladder and bowel, are held in place by ligaments and fascia, supported and mobilised by muscles. Our myofascial system is vital to our daily lives and integrates with our skeletal (bones), visceral (organs), gastrointestinal, neural (nerves) and emotional systems to function well. Our myofascial system is disrupted by surgery, as fascia and muscles are damaged during the surgery process – this is especially so in the case of stoma formation.

Parastomal hernia occurs in up to 50% of people after stoma formation, and refers to a bulging of the abdominal organs through the abdominal wall. Parastomal hernia arises due to weakness in the myofascial system i.e. muscles and fascia, caused by surgery. Sometimes, there is significant weakness in this area prior to surgery, due to factors such as pregnancy, previous surgery, obesity, sedentary behaviours, connective tissue type and/or recurrent straining (eg heavy lifting, coughing, constipation, straining to pass urine). Whilst it is best to be proactive and assess these factors with a pelvic health physiotherapist prior to surgery, for many ostomates it is not until after a hernia has occurred, that the need for physiotherapy assessment becomes apparent.

Pelvic health physiotherapists are specialised physiotherapists who have undertaken postgraduate training in issues specific to women’s, men’s and children’s pelvic health. We have expertise in assessing and managing problems related to bladder and bowel function, pelvic floor muscle weakness, pelvic and abdominal pain, and “core” rehabilitation. At Consano Pelvic Health Centre, our pelvic health physiotherapists investigate the systems within the body that may be contributing to the presenting problem, whether it is parastomal hernia, pelvic organ prolapse, constipation, soiling, urinary incontinence, abdominal weakness or sexual pain. We take time to listen and approach management holistically. We are very active in helping the body to heal itself. Our unique, specialty clinic caters for private patients seeking one to one consultations and/or exercise rehabilitation.

For more information or to make an appointment, please call Consano Pelvic Health Centre on 92745666 or email info@consano.com.au

Vaginismus

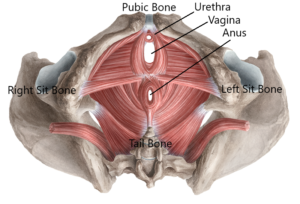

Vaginismus is a diagnostic term referring to the involuntary tensing of the superficial pelvic floor muscles. But what does this mean? How does it come about? And what can be done about it?

The pelvic floor is made up of a group of small muscles, in two layers. The pelvic floor muscles attach onto and are interwoven with fascia, which is a strong, flexible connective tissue found throughout the body including the pelvis. The two layers of muscles and multiple layers of fascia form a dynamic supportive base in the pelvis, allowing the bladder, vagina, uterus, ovaries and rectum to be supported and to move, when they need to. When one area of this dynamic “team” of tissues overworks, overstretches, struggles to work, or has too much pressure over a sustained period – symptoms arise.

Vaginismus refers to the over-tensing of the pelvic floor muscles located closest to the opening of the vagina, the perineal muscles (superficial pelvic floor muscles). Typically vaginismus has been thought of as a psychological or psychiatric diagnosis. Whilst this may seem confronting, the role of the pelvic floor goes well beyond a conscious, voluntary group of muscles that can be mechanically contracted and relaxed. Pelvic floor tension is integrally connected to emotions, as well as to the function of nearby organs. In adults, fascinating research evidence shows that the pelvic floor muscles, which are involved in elimination of urine and evacuation of faeces, are the first area in the body to tense when an individual is feeling unsafe.

Vaginismus can arise from a single trigger event, such as a traumatic vaginal examination, unwanted sexual activity, a life-threatening event, including sudden-onset severe bodily pain, or another traumatic experience. This persistent pelvic floor tension can begin in early childhood, for example following an experience of being frightened whilst in a toilet. Equally, vaginismus can commence during teenage years or adulthood. As the vulva and pelvic floor is such a private, unseen part of the body, women are frequently unaware of this tension in their pelvic floor muscles, until symptoms arise. For some women, this may be during a vaginal examination by a health professional. For others, it may be on attempting to insert a tampon or menstrual cup or have penetrative intercourse.

Symptoms of vaginismus include tightening and tensing of the tissues around the vaginal opening, soreness to touch, a blocking or “brick wall” feeling on attempt to insert anything into the vagina, pulsing, throbbing, burning and aching. These symptoms at the opening of the vagina may also be associated with persistent deeper pelvic tension, jaw tension, headaches, migraines, breathing pattern changes, and widespread bodily pain.

At Consano, our specialised pelvic floor physiotherapists consider the contributing factors to the tension, as well as current symptoms. We take a sensitive approach to assessing women who present with a diagnosis or symptoms of vaginismus, including to vulval and vaginal examination. Treatment is individualized and our practitioners are experienced at retraining the pelvic floor to release tension. With our holistic approach, women can learn to feel this part of the body and be instrumental in their own healing.

Our Approach

Our name CONSANO is the latin word for ‘to cure, heal, remedy and restore’.

This is the essence of what we do.

We use our specialised pelvic health physiotherapy training and our unique holistic approach to cure, heal, remedy and restore the pelvic health of our patients

Our Centre

Our Pelvic Health Centre in Guildford has been specially designed to suit the specialised requirements of our patient treatment rooms and classes.

Learn more